Relative price of services recovers after pandemic

The prices of services in the Netherlands are rising faster than the prices of goods. This trend was temporarily broken during the COVID pandemic due to supply chain issues, as revealed by new DNB figures.

Published: 21 January 2025

© ANP

Relative price increase

The price increase of a product or service compared to other products or services is called a relative price increase. Examples include chocolate or bungalow park prices, which have recently risen faster than the general price level. After a temporary trend break during the pandemic, the relative price of services compared to goods has returned to its long-term trend. Central bank monetary policy is aimed at a stable development of the general price level and, in the long run, has only limited influence on relative prices in the economy via the key policy rate. However, temporary deviations from the long-term trend provide insight into the dynamics of inflation.

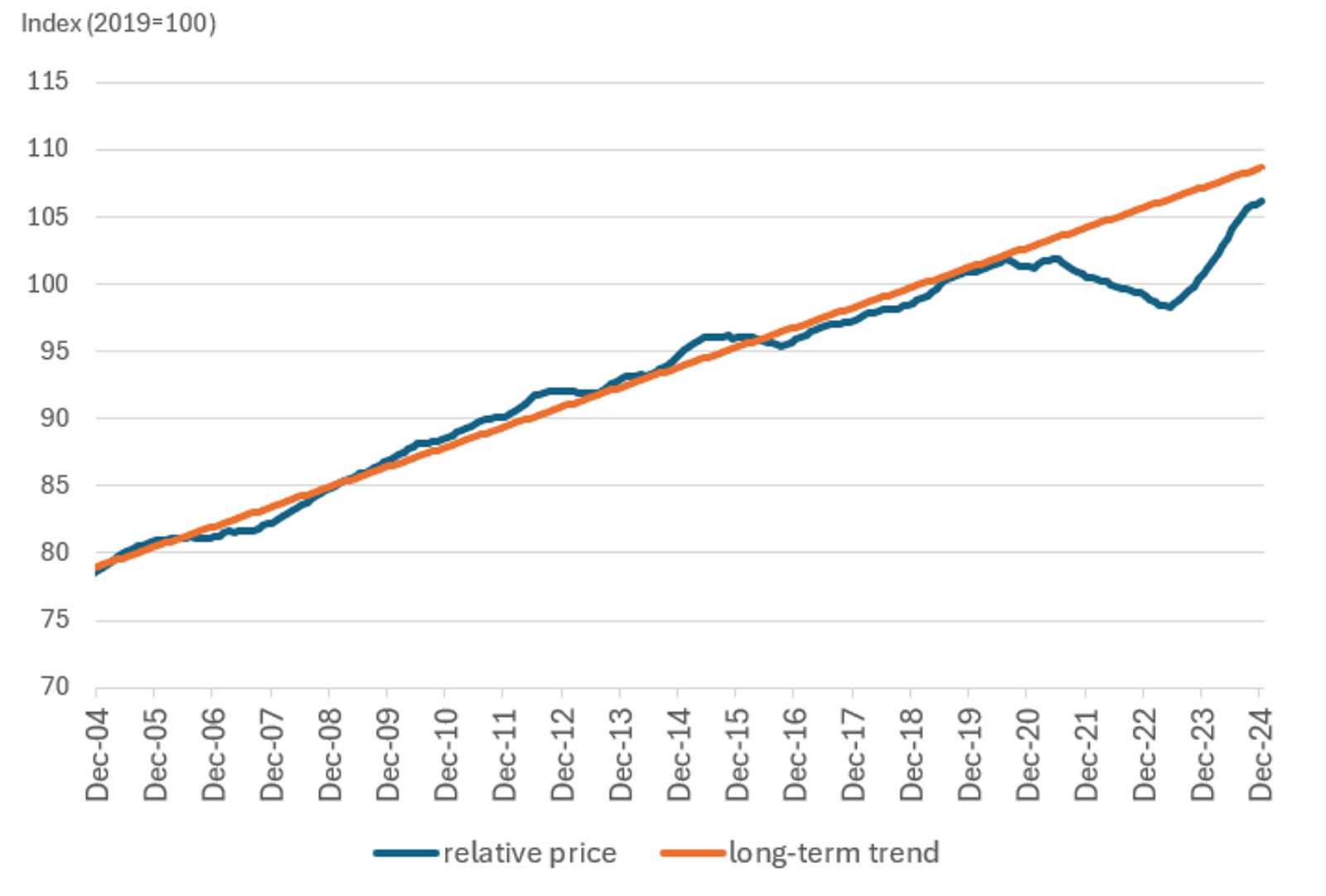

Figure 1 - Relative price of services compared to goods

© DNB

Note: Ratio of prices (HICP) for all goods and services (excluding food and energy). Figures are seasonally adjusted on a monthly basis. Base year: 2019. Six-month moving average. Linear trend estimated over the period 2002-2019.

Long-term trend

Prices of services tend to rise faster than prices of goods. The relative price of services compared to goods therefore rises faster over the long term. There are two main reasons for this trend.

First, the demand for services has been steadily increasing in recent years. As incomes rise, people spend relatively more on services, which drives up their prices. Relative to goods, consumption of services in the Netherlands has increased by about 10% over the past 20 years.

Second, productivity in the goods sector tends to increase faster than in the services sector. This allows goods to be produced more efficiently over time and reduces the prices of goods. Moreover, goods are more tradable than services. Competition in international markets and increasing access to lower labour costs abroad are additional factors that push goods prices down.

These factors ensured that goods inflation remained low prior to the pandemic, while prices of services continued to rise steadily, as the trend in Figure 1 shows. This resulted in a long-term upward trend in the relative price of services.

Pandemic shock and recovery

Between 2021 and 2023, the trend in Figure 1 was temporarily disrupted by two major shocks: supply chain disruptions and the energy crisis (Figure 2). Both shocks caused sharp increases in goods prices. At the same time, pandemic containment measures reduced demand for services, such as hospitality and travel, while demand for goods increased. The shift in demand from services to goods contributed to the temporary drop in the relative price of services. This deviation from the trend coincided with the recent period of high inflation, peaking in the second quarter of 2023 when services inflation was over 7%, and goods inflation over 8%.

In the spring of 2023, a phase of normalisation began in the Netherlands, as in other countries. Energy prices had fallen after peaking in late 2022, and supply chain issues had been resolved. As a result, goods inflation declined while the price of services continued to rise sharply, driven by increasing demand. As shown in Figure 2, this led to an increase in the relative price of services from the summer of 2023, although it continues to remain below the long-term trend. At the same time, core inflation fell and is now closer to (but still above) pre-pandemic levels. Stubbornly high services inflation thus coincides with the return of the relative price of services to the long-term trend.

Figure 2 - Relative price of services and core inflation

© DNB

Outlook

Despite the current phase of normalisation, it is uncertain whether the relative price will return to its pre-pandemic trend. The pandemic was a major shock that changed consumer behaviour and weakened consumer confidence. Productivity growth and international trade flows have also been affected, which can lead to higher goods prices. In addition, services inflation is strongly related to wage developments, which may also have changed due to greater labour market tightness. Substantial wage growth may lead to higher prices of services, especially as the service sector is comparatively labour-intensive.

In the years ahead, deglobalisation and geopolitical developments could strongly influence the prices of goods and services. Trade tariffs or higher transport costs could hit the international goods trade, which has kept goods prices low in recent years. As a result, tradable goods may become more expensive in the years ahead. We have also become increasingly dependent on foreign suppliers for key digital services and social media, meaning we are more likely to be confronted with the prices or rates they charge. Meanwhile, digitalisation continues to boost digital services supply and demand, and these services are claiming a bigger share in the inflation basket. Services are also becoming increasingly internationally tradable, especially thanks to the internet and perhaps AI in the future. This could impact future price dynamics. An increase in supply and competition from abroad puts downward pressure on prices, while higher demand leads to higher prices.

Higher temperatures, altered precipitation patterns and extreme weather events due to climate change could significantly affect food production in the coming decades, leading to a relative increase in food prices. The relative price of energy may also change due to the energy transition, for instance if carbon taxes boost prices. This further clouds the outlook.

Discover related articles

DNB uses cookies

We use cookies to optimise the user-friendliness of our website.

Read more about the cookies we use and the data they collect in our cookie notice.